The Yamagata Film Criticism Workshop has taken place during the YIDFF since 2011. This project encourages thoughtful writing on and discussion of cinema, while offering aspiring film critics the chance to immerse themselves in the lively atmosphere of a film festival. Co-presented by YIDFF and Festival Film Dokumenter, the Film Criticism Workshop moves to Jogyakarta. It’s a 6-day class filled by learning how to write film criticism with two mentors: Chris Fujiwara (USA/JAPAN) and Adrian Jonathan Pasaribu (Indonesia) during the Festival Film Dokumenter in Jogjakarta, Indonesia, Thursday, 6 – Tuesday, 11 December 2018. The final essay written by the seven international participants are introduced on this website. Here, “A Journey through Home Movies: Agustina Comedi’s Silence Is a Falling Body” by Satoko Tomishige.

A Journey through Home Movies: Agustina Comedi’s Silence Is a Falling Body

Satoko Tomishige (Japan)

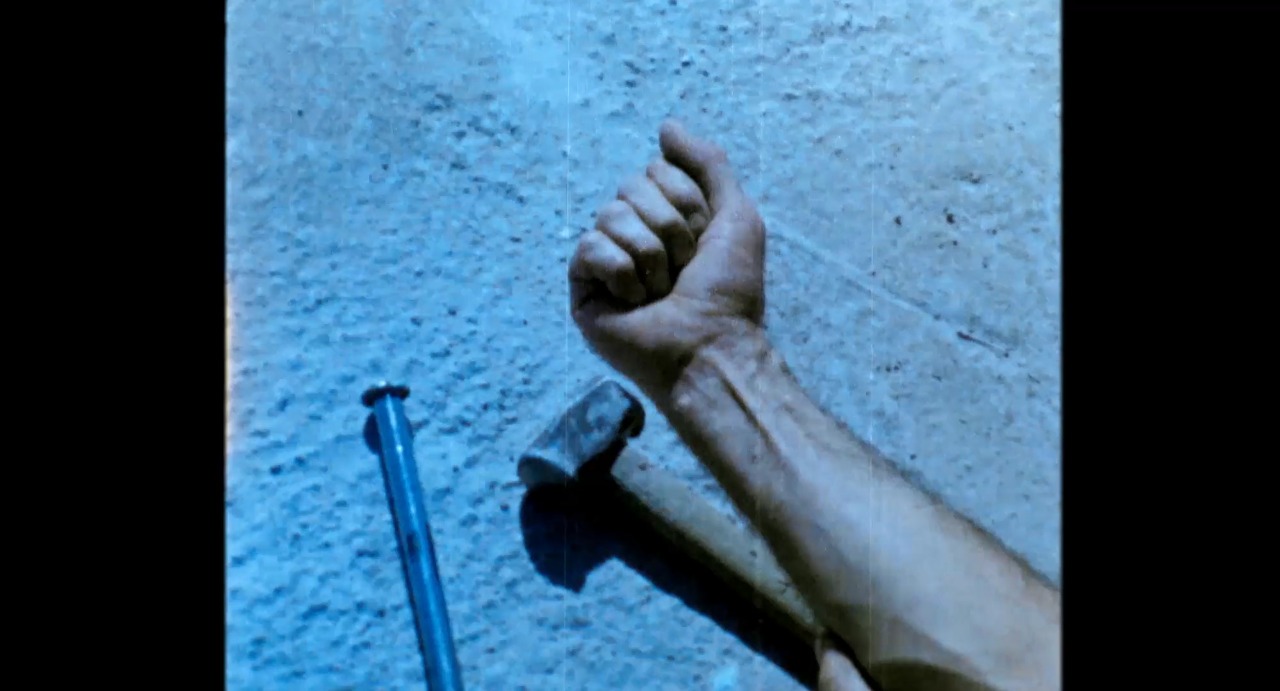

Home movies have been becoming more and more visible as production material in filmmaking, especially for documentary and experimental films. This is partly because these small materials have the potential for amazing discoveries, although they are fragile and easily lost. Projected after being unseen for a long time, forgotten images flood over us and images provoke our memory in many ways. A case in point is Silence Is a Falling Body. Agustina Comedi found a pile of videotapes and films her deceased father, Jaime, left, and she decided to make a film from them.

This film seems to be an audiovisual journey to find the truth about Jaime, driven by a personal motivation arising from Comedi’s deep affection for him. The film explores his life before his marriage and after his daughter’s birth — namely, both what has been unknown and what has been known to the director. She uncovered many videotapes, contacted Jaime’s friends and ex-lovers to interview and shoot, and edited together a collage of archival and new footage. Perhaps because it was risky and uneasy for Comedi and for her family to reveal Jaime’s past, she has left many traces of the hesitations, shudders, and surprises they experienced in the course of searching. We can see these traces not only in the interviews in which they show their feelings, but also in Comedi’s deliberately staged acts of editing; pauses, rewinding, close-ups, and repetitions, accompanied by beeps, clicks, and other sounds of audiovisual equipment in operation. The film never ignores emotional responses, but rather preserves them one by one with each discovery. As a result, the film can sustain an intimate atmosphere without giving an impression of indecency, even when it approaches Jaime’s personal life most closely.

The journey this film attempts also pushes a way through the societies and cultures where Jaime had lived. The 1980s in Argentina were a politically stormy period with an awareness of diversity and individual freedom. The film finds Jaime’s active figure in social movements and glittering gay cultures. In some footage, he shot his friends as queens on the night stage; at other moments of the film, his friends tell how they spent time together in political meetings that he organized, or on a trip, which is shown in color slides. As the director gains more details of Jaime’s hidden life, suspicion causes the tie between daughter and father to loosen. In an interview, Jaime’s old friend, recalling how he eventually slipped away from their society after his marriage, says, “he was taking care of something else.” The next scene shows a girl playing a violin on stage: the filmmaker dares to post her image to that place. Now, the presence of herself as daughter comes into question – a progression driven by her painful but inevitable desire to ask what she meant to him. At this point, the search for him moves ahead but becomes more complex. Is she looking for the unknown face of Jaime? Or does she want to look for him still as her father?

The director divides an important scene in two, placing one part at the beginning of the film and the other nearly at the end. This is a nostalgic home movie shot by Jaime on a visit to a museum with his family. A shaky handheld camera slowly captures every detail of Michelangelo’s sculptures. The director lets the shot run longer than she usually does. This scene tries to present Jaime’s vision so that the viewer can experience it through his eye. The image captures almost precisely how he gazed at these sculptures, tracing his response to their physical male beauty, which he filmed with the very same hand that filmed his daughter and his family. Here the film reaches a crucial point of its journey, as the director struggles as a daughter with a crack in her father’s image. With which figure should she identify Jaime: as her father, or as an unknown man, whose life the film reveals?

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)