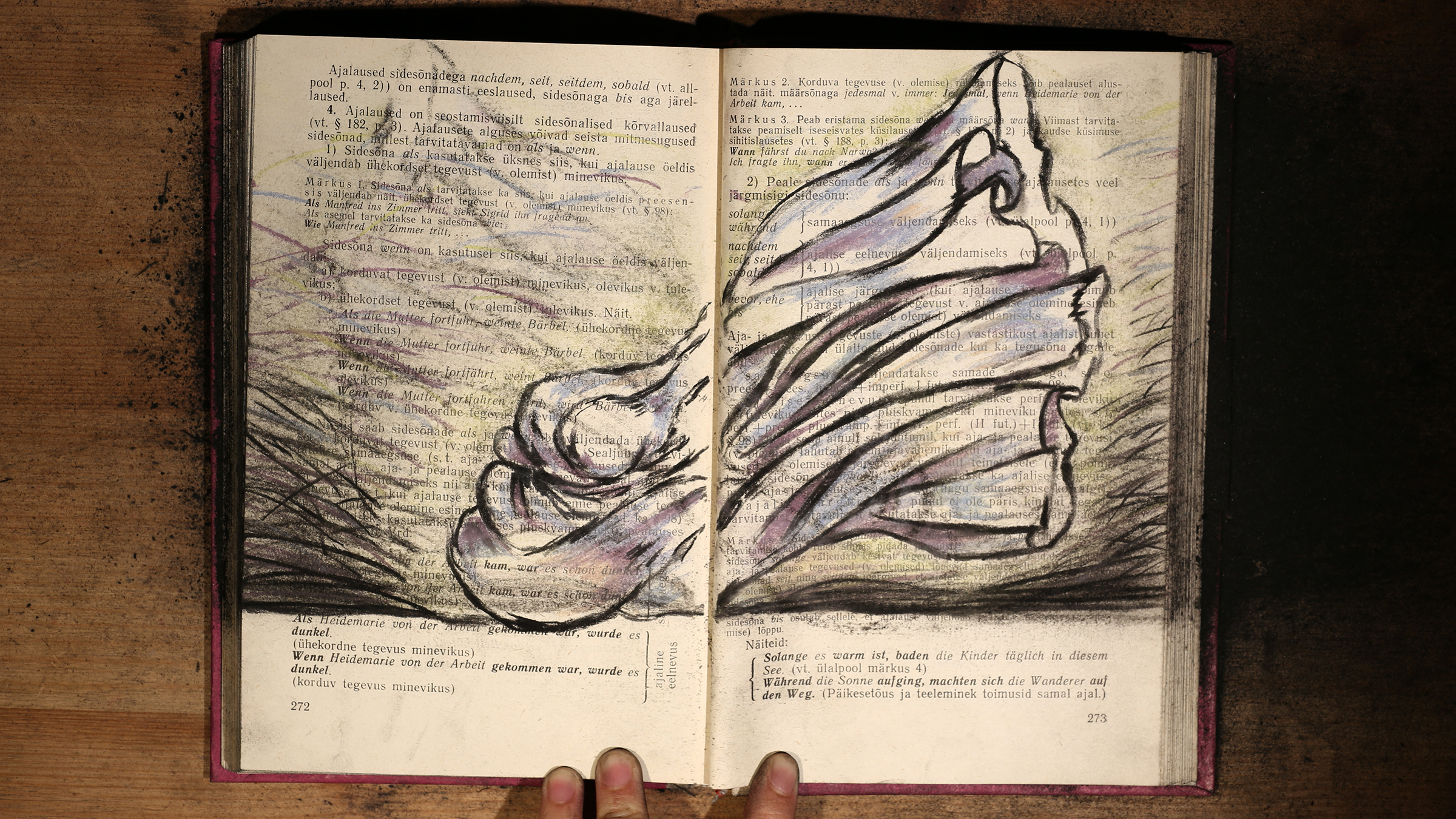

In The Last Visit (การพบพาน…ครั้งสุดท้าย, 2024; YIDFF 2025 New Asian Currents), Thai animator Keawalee Warutkomain turns grief into a tactile experience. The 16-minute short grounds us with a picture and a brief dedication, before unfolding entirely in animation form within the pages of an old Estonian book, its title meaning “Village” or “Visit.” Across its yellowed paper, Warutkomain’s charcoal drawings appear, dissolve, and return, filmed in delicate stop motion. We never know what the printed text says, and that omission is part of the film’s aesthetic: the abstract drawings made on the book’s body matter more than its words. Its premise is deceptively simple—a young woman recalls a loss she could not physically witness while abroad. But Warutkomain’s narrative and stylistic choices do more than evoke remembrance—they create a form of survival against forgetfulness.

The choice of charcoal as the film’s medium feels almost autobiographical; it is never fully erasable, always leaving a smear, a residue that stubbornly refuses to disappear. Across the pages, lines and abstract shapes dance and dissolve—black ink spills across the frame in blobs that bounce around, messy interlaced lines forming brief, rhythmic patterns, sometimes taking the form of recognizable figures: a child on a swing, a hospital bed, a face—only to be erased and drawn again over the silhouette of what came before. In The Last Visit, that trace is a metaphor for grief: even when the image is gone, its ghost remains. The lingering smudge of the erased drawings resembles the afterimage burned into the retina after looking at something too bright—a fleeting impression that outlives the moment. The blackened piles of eraser dust that accumulate on the page are reminders of the persistence and care required to keep a memory alive after its subject has vanished. Warutkomain captures not the act of remembering, but the movement of memory itself—less a reconstruction of who was lost than an observation of how recollection changes shape. The film turns into a quiet anatomy of memory: how it slips, overlaps, and leaves traces on those who hold it.

The sound design furthers the movie’s sense of intimacy. The film contains no dialogue or voice-over, yet it is far from silent. The soft scratches as she draws another line, the rustle of paper, and the low hum of distant trains and wind immerse the viewer in a tactile, almost haptic world. These sounds are familiar and comforting, but they gain an uncanny weight when layered with the dark shadows of the drawings. In the absence of voices, The Last Visit makes us pay closer attention to the images—but soon the sound transforms. What felt incidental is now inseparable from the experience of watching, and we grow accustomed to that sound much like we grow accustomed to death: not because the noise grows quieter, but because it becomes part of our inner rhythm.

The book serves as a vessel of memory, its pages turning, revisited, and flipped back and forth in restless loops. These movements reflect the cyclical rhythm of grief—the constant urge to return, relive, to undo. This choice speaks to the kind of documentary The Last Visit wants to be. Unlike archival footage, which freezes time to show what happened, Warutkomain’s animation documents what cannot be seen: the inward, repetitive labor of remembering. She sets aside the traditional tools of documentary not to reject reality, but to suggest that grief resists documentation. Facts cannot hold the anguish; only gestures can. Her drawings, erasures, and hesitations are a form of fieldwork—an intimate record of how absence leaves marks. Animation here is not fabrication but evidence: it preserves the trace of her own hand, turning emotion into a testimony.

Lorena Sampaio

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)