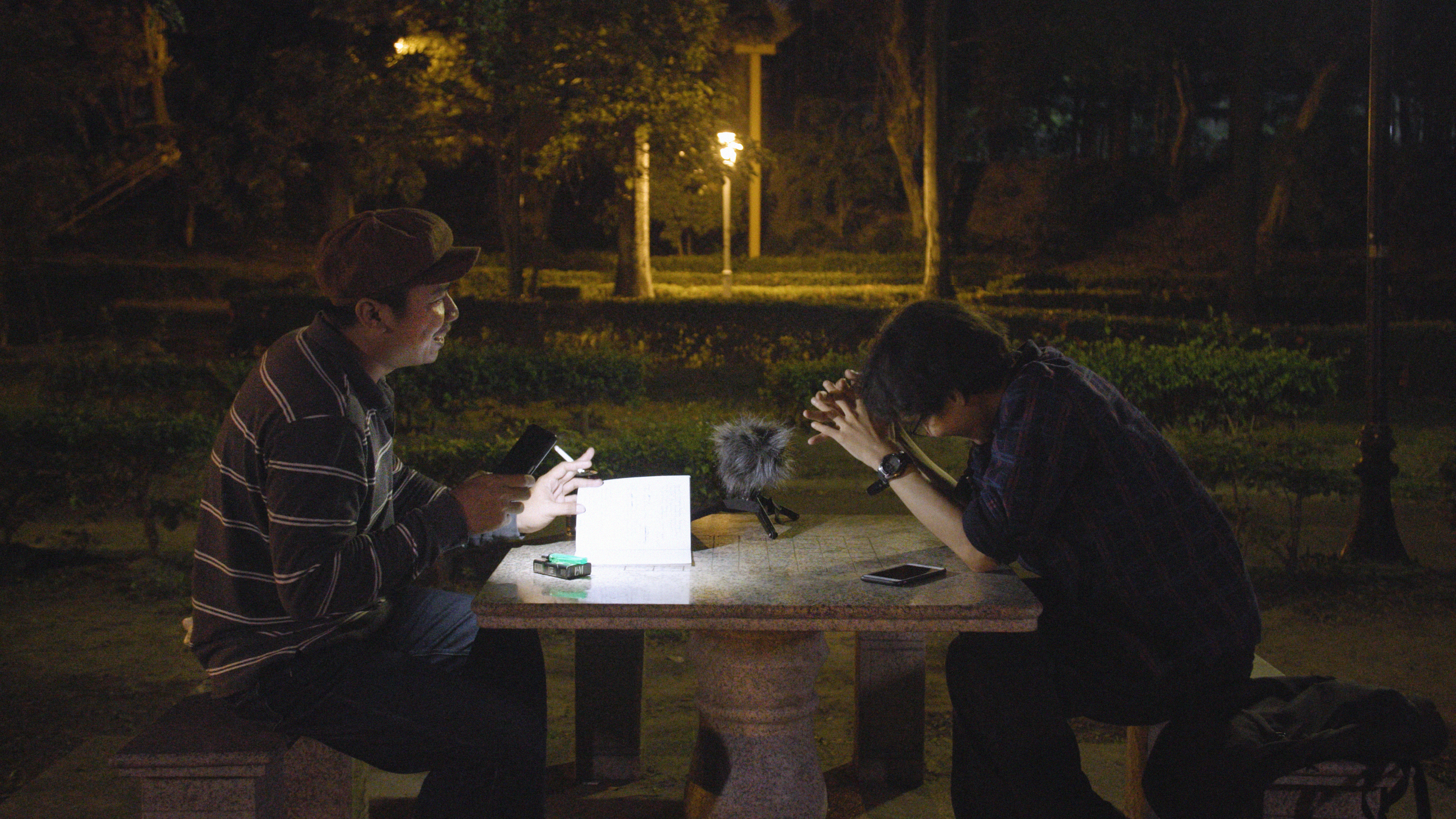

So Yo-hen’s Park (公園, 2024; YIDFF 2025 International Competition) opens with two Indonesian migrant workers in Tainan Park, reciting poetry, filming one another, and slowly blurring the line between performance and observation. The poems they recite are newly written for the camera—improvised fragments of longing, labor, and humor. So, it gives them free rein to shape their performance, lending the film a sense of co-authorship that is rare in observational documentaries. Under the faint light of street lamps and their phones, the men frivolously carry only a microphone and an idea, their voices mixing with the sounds of the passersby, night insects, and distant traffic. This minimal setup feels fresh and captivating. The park becomes a stage where fragments of friendship and language intertwine, telling the stories of and shaping a community that doesn’t yet know it is one. The camera, patient and unintrusive, watches them with tenderness. For a while, the film feels still, bright, and pleasant.

As migrant laborers, Asri and Hasan spend most of their days unseen; their leisure is confined to public spaces like this. The park becomes both refuge and stage. But as time passes, the spell begins to dissolve. Park runs for over ninety minutes, and by its second half, the film starts to collapse under its own repetition. It circles back on itself—gestures and lines repeated with little variation. Shots of benches, lampposts, statues, and puddles begin to blur together. A conversation about what they are doing returns, slower, almost drained of conviction: the park starts to feel suspended in time. Even the subjects notice this fatigue. At one point, they admit that everything “has been going round and round in circles,” that the film itself is “becoming more and more unclear,” joking that “there’s always a message to convey—in this movie, we don’t know what it is; maybe the audience will figure it out by themselves.” It’s a moment of brutal honesty that exposes the film’s self-awareness and problem. Park recognizes its almost Sisyphean repetition—an endless reenactment of purpose without progress—but stays inside it.

There is an irony at the core of the movie. It deliberately rejects narrative structure and resolution, yet this pursuit of total freedom becomes a constraint. The more the film insists on escaping norms, the more it traps itself in a loop of self-awareness. Repetition, at first poetic, turns mechanical. The rhythm slows until it resembles stillness. What remains is atmosphere without evolution—a film recycling its motifs and leaning on well-shot stills. Perhaps this exhaustion is not a limitation but an intent: a reflection of how freedom, when untethered from purpose, collapses into its own inertia.

Still, it would be unfair to dismiss Park. At its core, it is a deliberate and tender work—ambitious in form and sustained by the magnetic presence of its two collaborators. When the film works, it finds fleeting moments of genuine beauty: a half-lit smile, a verse carried by the rain, a sense of companionship that feels accidental and sacred. Their verses, spoken in Bahasa Indonesia and Mandarin, fill the night with echoes of labor and belonging. By the film’s end, the community they’ve built—the small world of the park—briefly feels real. Then one leaves to return home, and the other remains, framed against the same bench where they began. Once a playground for imagination, the park becomes a space of waiting again. Its characters speak of things “going round and round in circles,” of everything “becoming more and more unclear,” and the film seems to absorb those words into its very form. Park begins as a gesture of freedom and ends as a study in exhaustion. Ultimately, it becomes a record of its own making—a portrait of creation consuming itself.

Lorena Sampaio

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)