1. The world is all that segments and eludes the gaze.

1.1 Perspective is conical.

1.1.1 The closer an object is to the viewer, the sharper its details are. Anything further than sixty degrees from the viewer runs the risk of blur and distortion. There is always a limit to individual perception, to one’s field of vision.

1.1.2 The possibilities of film, the future of the world at large, is hyperbolic and riddled with asymptotes.

1.1.3 The case, a fact, is a circle.

1.1.3.1 Photodiodes are twinkling circles.

1.1.3.2 Cinema is trillions of circles that dance in the darkness.

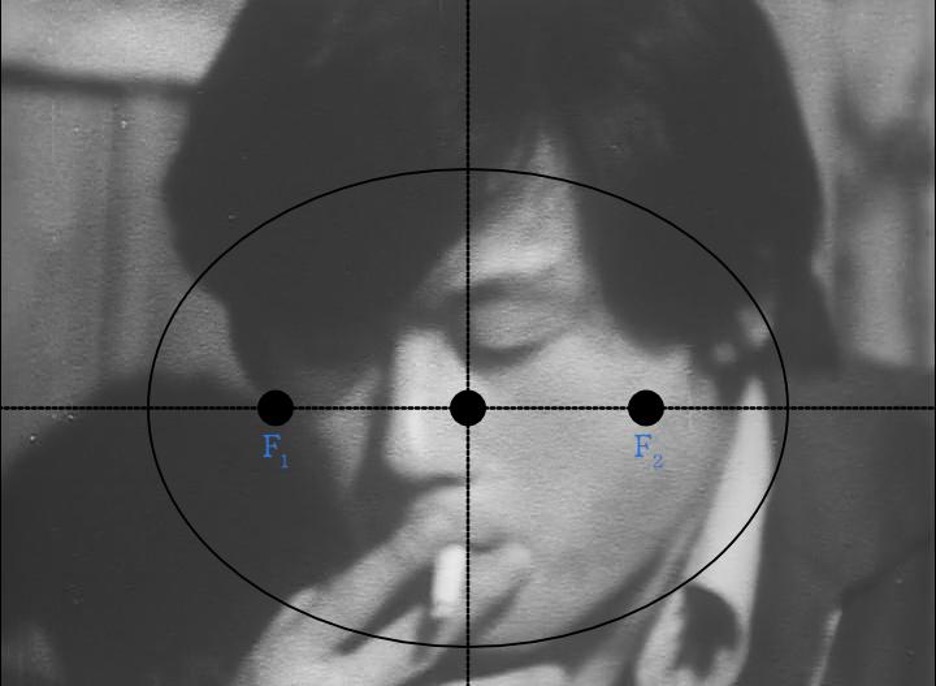

1.1.4 A film is always made in parabolic circumstances, though its end result, its document, is always an ellipse.

1.1.4.1 Criticism is parabolic, extrapolating beyond what is shown to what it believes is the case while breaking down gazes.

*

In the tenth scene of Narita: Heta Village (Sanrizuka Heta buraku, 1973; screened at YIDFF 2025 in the Special Invitation Films section), before the Public Hall and a bonfire, farmerettes and idle men clap and cheer for a honking automobile emerging from the darkness. Two passengers step out from the car: Uryu Masahiko and Ryuzaki Haruo. Both are all smiles, though one youth appears more relaxed than the other. As Haruo issues breathless, formal expressions of gratitude to the chattering womens’ adulations, Masahiko, in between brushing his bangs past his eyes and taking a drag of the cigarette affixed in between his fingers, settles for a singular thank-you. “Do you think I’ve gotten fat?”, he asks someone offscreen.

The camera pans left, revealing Ryuzaki Katsue, Haruo’s father, bowing before Ogawa Shinsuke, the director of the film, thanking him “for everything.” Ogawa, having just exited the vehicle, bows even lower than Katsue. Beside them, the father of Masahiko, Uryu Hikoshige, exchanges another wordless greeting with an older man.

Through the intertitles and the constant buoying of the one-shot take between the three groups—Haruo and the women; Masahiko slightly apart from everyone else; and the middle-aged men—comes the new information about the twenty-eight boys who accompanied Masahiko and Haruo in jail. They were all detained by the police under false charges of an “assault that resulted in death” during the ongoing protests between Sanrizuka and the Narita Airport. By October 3rd, the day of this shoot, all boys have been released. Ninety days have passed since their initial arrest, back in June when the watermelons in their fields had turned ripe for picking.

In the documentary, the three scenes between Masahiko and Haruo’s arrest and the present show two different town meetings in the same house, with the villagers still in summer clothing. The third scene features light gossip among women harvesting rice from their now errant neighbors’ fields. The camera’s and the editor’s foci compress the month that flew by, bridging the absence of the two boys in a temporal ellipsis in between their labors within the Sanrizuka movement.

The succeeding sequences—the speeches from both fathers, the brief words of the emancipated detainees, and the conversations after the dinner—are all captured by cameraman Tamura Masaki and sound recordist Kubota Yukio. At the dinner, Ogawa can no longer be found. With six years of practice under their belts, Tamura and Kubota are more than capable of capturing the vulturous moths whizzing around the humble banquet and the men who yawn and check their watches. Tamura never strays from his position by the table, close to the left corner of the room. He’s attuned to the shifting rhythms of the room. After Hikoshige’s speech, Tamura registers the mutterings between the men to his right and pivots the camera, just in time to catch Katsue stand up and begin his own speech.

In a conventional documentary or piece of propaganda filmmaking, the film could have ended right at the moment Masahiko and Haruo stop speaking. Instead, the scene stretches on after dinner, when the clinking of plates and bottles cedes to the rancor of conversation.

Tamura and Kubota choose to focus upon Haruo first. He’s engaged in conversation with an older man. Later on, a brief cut introduces his father into the frame. Haruo’s impassioned vows to stand his ground and contribute to the cause as well as his detailed personal anecdotes relay his earnest sincerity and commitment to the village. He never breaks eye contact with whomever he speaks to with his whole chest. A casual disclosure of his nightmares while in jail reveals that he fears being “a man without substance” if broken apart from the Sanrizuka collective, when each of his ties to each person inside Heta Village have been neutered in his hypothetical scenario.

The most interesting part of this scene is that while Kubota’s microphone is affixed close to Haruo and Katsue, during the Yakuza anecdote, Tamura’s camera drifts to Haruo’s left where Masahiko is, once again, smoking a cigarette. Masahiko occasionally participates in the conversation or passes over the kettle to someone else, but similar to his demeanor upon his arrival, remains reserved.

Although Masahiko could have spoken more about his experience or other topics within the copious footage within the Ogawa Pro’s hands—especially since his frequent overnight stays at their house indicate a solid rapport established between him and the crew—his silence here is deliberate image-crafting from the director’s and editor’s end as opposed to a mere whim of Tamura. Thus, when Haruo speaks about his nightmares, his transparency overlays Masahiko’s opacity. Does Masahiko also shudder at the thought of being outcast like the Niya family, which, we were told at the beginning of the film, suffered ostracism?

Masahiko’s subdued presence at the table indicates some level of care to showing up, at least. There’s more than enough room for the audience to fill in their own gaps, elevating this moment to an ambiguous closer of the film’s narrative. This sequence appears to be the most contemporary within the documentary, juxtaposing Haruo’s communal spirit with Masahiko’s solemn face and cigarette smoke—the collective looming over the interior of one of its individuals.

Within the filmmaking language, an ellipsis is conventionally used to demonstrate the cuts and other methods that coarct time. But within the grammar of Heta Village, especially within the Japanese context, it can be used as a visual shorthand for silence. The second chapter of the film, where the villagers discuss the unexpected sale of a plot of land where graves are located, also plays with ellipses within its latter definition—a happy accident discovered by Ogawa Pro as they began the habit of continuing scenes after the initial discussion had ended. However, the final scene with Masahiko is the first time that the privilege of ellipsis is given to an individual. While other individuals are highlighted within the documentary, such as the old man introducing the village in the beginning and the grandmother’s interview in front of her house, they’re all open to the filmmakers and share their thoughts unhindered. An ellipsis in this sense can be perceived as time weaving in and out of the contours of the three or six dots. This doesn’t follow the standardized throughline of Point A to B, but the ebbing motion of a lull, of contemplation.

*

2. Let the unspoken pass in silence, the surrendered lapse unto quiescence…

2.1 Haruo’s four blinks cut to the intertitle and the shadows of shumokus swinging past Chekhov’s sutras… drums and matronly chants parallel the pulsating ellipses of Masahiko’s and Haruo’s previous ellipsis…

2.1.1 Thud, thud, thud…

2.2 Restraint is an insurmountable imperative for someone who, if given parabolic privileges, could continue…

Alyssandra Maxine

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)